Roger Savage

So many international awards… so little cupboard space. Andy Stewart talks to Australia’s most decorated film mixer about operating Soundfirm and what’s involved in delivering great sound to a cinema audience.

Though he’s been responsible for mixing some of Australia’s most iconic films, as well as several international blockbusters, Roger Savage is one of the most unassuming individuals you’re ever likely to meet. With a list of film re-recording and mixing credits that would happily roll for as long as it takes to clear the average cinema, Roger could be forgiven for having at least some sort of ego, some semblance of arrogance. But if the way he displays his impressive collection of AFI and BAFTA awards is anything to go by – piled unceremoniously on top of a cupboard in his office like empty beer bottles – Roger, it would seem, is not exactly one for blowing his own trumpet. Perhaps the best way to illustrate what appears to be Roger’s almost total lack of self-promotion is his daughter’s recent discovery of her father’s Moulin Rouge Academy Award Nomination certificate for Best Sound (2001), hiding in a cupboard at her house.

Roger Savage has presented the soundtrack of dozens of films to countless millions of moviegoers for well over two decades now. But his illustrious career in sound actually began back in ol’ Blighty in the ’60s where he most notably recorded the likes of Dusty Springfield and the Rolling Stones. In fact, Roger recorded the Stones’ debut single, a cover of Chuck Berry’s Come On, at Olympic Studios in London “for nothing,” as he puts it. “From memory they had no money to pay for the session, so we sorta crept into Olympic late one night.”

His own show reel highlights package includes all the Mad Max films, Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi, Dead Calm, Romper Stomper, Strictly Ballroom, Muriel’s Wedding, Romeo + Juliet, Jackie Chan’s First Strike, Babe: Pig in the City, Snow Falling on Cedars and Moulin Rouge, just to name a few!

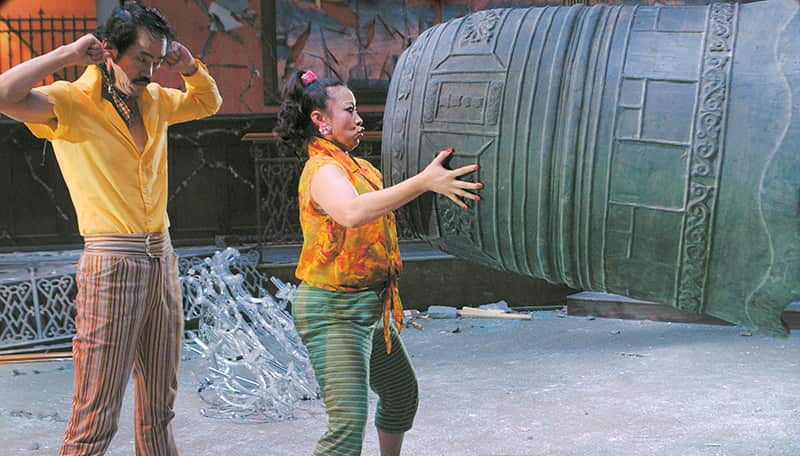

But it’s been interesting to see where the road has taken Roger over the last few years. Although he remains Australia’s pre-eminent film soundtrack mixer, and has applied his skills to some of the most notable recent Australian film successes, it’s Asian films that have benefited most recently from his handiwork. Throughout the ’90s, he, along with his post production company Soundfirm, did a number of low-budget Chinese film soundtracks inside the Soundfirm studios in Melbourne, many of them starring Jackie Chan. And more recently these have included films such as House of Flying Daggers (for which Roger recently won a US Golden Reel Award and was nominated for a BAFTA award), Hero, and the currently screening Kung Fu Hustle. I caught up with Roger at Soundfirm’s Melbourne studios recently to find out how one survives in a ‘House of Flying Daggers’…

SINO CINEPHILE

Andy Stewart: So Roger, how is it that you appear to have become Chinese filmmakers’ mixer du jour?

Roger Savage: Well, we’ve been doing Chinese films for about 10 years now – Soundfirm’s first Chinese film was Rumble in the Bronx with Jackie Chan in 1995-96. We established a bit of a reputation there through that film’s success. It was a very low-budget film with a great soundtrack, which is unusual. When it was released people inevitably asked ‘where did you get that soundtrack?’ and the answer was, ‘in Australia’. Soon after that we started doing a lot of low-budget films and some Mainland Chinese work. One of these low-budget films was directed by Zhang Yimo, who directed Hero in 2004. It was through this previous association that we found ourselves working on that film as well. Hero was quite an unusual soundtrack, not your typical Hollywood soundtrack.

AS: In what way was the Hero soundtrack different?

RS: The Chinese directors don’t bow down to the studio system, they don’t have to, so they make their films the way they want. Often the films themselves are way out there, which often means the soundtrack is as well. And they’re very spiritual in a way. Most ‘western’, or American action films we’ve worked on differ from their Chinese equivalent in that you can always count on music running through an American action sequence – always – and the Chinese don’t necessarily do that. For instance, in House of Flying Daggers, which I mixed here in 2004, there’s an action sequence in a forest which contains very little or no music. It’s quite a heavy action sequence and without music to fall back on, it was difficult to keep the momentum going. You tend to rely on music almost like a crutch to keep the tension high and momentum flowing. The mixing then simply involves creating ‘vertical’ sounds that pop up through it.

AS: So how does that affect your approach to mixing, not being able to rely on music underpinning these action sequences?

RS: It changes your mixing and sound designing quite dramatically. It’s more difficult to pull off because you’ve got to have every base covered. You can’t simply hide problems you might be having behind a hyped-up music score. What’s more, the Chinese directors, more often than not, aren’t hands-on throughout the process, mainly because we’re here in Melbourne and they’re in China. So we have to come up with the goods without them. But interestingly, the last three Chinese films were entirely ADR’d. There was no sync sound, which made my mixing role a lot easier. It was all manufactured in the studio so we actually started with complete silence.

AS: Are you saying that these film productions don’t even bother to record the location sound?

RS: No, they record it, and in fact the Chinese sound recordists are probably the best there are. They’re incredible. But the main reason most of the more recent Chinese films are post-synced is because often the actors they use can’t speak very good Mandarin – their native tongue is often Cantonese, Korean or even Japanese. In House of Flying Daggers, for instance, some of the main actors were Korean and Japanese whose Mandarin was unacceptable to the Mainland Chinese audience. To satisfy the Chinese audiences the production hired voice artists to come in and redo the voice at our studio in Beijing. The Chinese editors then expertly cut the voice back into the film – they did an amazing job. Neither House of Flying Daggers nor Hero sound or look like a dubbed film at all.

AS: What’s involved in good ADR in your experience and how does that affect your job as the mixer?

RS: Hero was entirely dubbed and yet you’d swear it was sync sound because the ADR cutting is almost perfect. The Chinese editors are so accurate; they put most of the world to shame. A lot of trouble was also taken to get a good voice actor in to replace the voice, because in the end it’s still up to the actor to supply the editor with good performances. The problems with voice mixing in film are mainly to do with matching the sync sound to the ADR, particularly if the switch between these two sources is being made mid sentence. A multitude of problems arise in that situation. But the most significant of these is actually faced by the actor, who is often made to come into the studio – often six months later – and somehow get back into character long after they’ve left that role behind. It might be cold, or early in the morning or whatever… and all these different circumstances conspire to affect the tone and pitch of the actor’s voice. Consequently, it’s then the job of the film mixer to technically match those sounds – often a very difficult task. The other issues are of course the environments of the original film set, which are often noisy. Then there’s the location mic, which may consist of a crappy radio mic or whatever. Most films are a hotch-potch of the two recorded voices [location and ADR], and making the two flow seamlessly into one another is the hard part.

AS: Is matching these two voices simply a tonal (EQ) problem or is there far more to it than that?

RS: Matching the two voices is an EQ and a reverb thing mainly. The difficulty is in getting good small artificial room reverbs to match the sound of the real rooms recorded by the location mic. For instance, in this room here where we’re talking, the small reverb sound created by this office space is hard to reproduce with a reverb program or processor. There aren’t too many reverb units capable of good small room sounds, in my opinion. The digital plug-in I like best is probably [Audio Ease] Altiverb. That’s very good at reproducing small rooms quite naturally.

AS: Is there enough effort made nowadays to get decent sync sound on the set in the first place or are film makers becoming utterly dependent upon ADR?

RS: That does happen. Certainly some directors are more determined than others to capture good quality sound on set. But it’s a losing battle most of the time. First of all there are often too many wind machines and other mechanical devices on set that prevent the sound recordist from capturing good sync sound, no matter how determined they might be. In that circumstance, there’s very little anyone can do about it, and what is captured becomes a guide track. The main problem is always getting the mic in close enough to the actor – it’s the bane of the sound recordist on a film set. Often he or she gets ‘shoved’ and the priority is given to the visual image, the comfort of the actor and the practicalities of the various mechanicals that produce the life-like set (i.e., wind machines etc). But there is a movement starting to make up some ground that’s been borne out of the adoption of these new generation multitrack digital recorders, like the HHB PortaDrive, to allow sound recordists to capture decent sync sound with new remote mics with digital transmitters like the DPAs.

I mixed a Chinese film in 1999 called Road Home that was recorded using a Fostex PD6 multitrack. I can still remember the day the sound recordist came here with the tracks he’d recorded; he had all the different mic channels labelled. When I first pulled the sounds up on the console and compared the radio mic to the boom mic I couldn’t tell them apart. I said to him, ‘this is not a radio mic, surely?’ because I’m used to radio mics sounding pretty awful generally. But he insisted, ‘no, it’s a radio mic!’. Anyway, it turned out to be a DPA4060 and it sounded fantastic. He’d placed the mic on the actor’s head just under the hairline and it sounded fabulous. When I finished mixing that film I recommended the DPA to the [Academy Award-winning] sound recordist, Guntis Sics, for Moulin Rouge, which he subsequently used. That made my job of mixing Mounlin Rouge a lot easier.

ILLUSION & SPACE

AS: We touched on reverb earlier, can you tell me more about what you’re looking for in an authentic-sounding reverb?

RS: Well it’s all about gluing the sound you hear to the visual cues you’re getting from the on-screen environment. I particularly like 5.1 reverbs these days because they’re great at creating spatial realism. Large halls, underground carparks and large interior spaces are pretty easy to recreate with surround reverbs. The exterior/outdoor reverb spaces are the more difficult ones to make sound natural. For instance, when you’re in a forest there’s definitely a reverb there, but recreating that natural space digitally is very difficult, both to imagine and create. If you’re trying to recreate an urban setting where there’s a voice bouncing off a building, or you’re mimicking the sound of a large canyon, that’s much easier because it’s primarily about a slap delay that’s simple to manipulate. But a natural sounding forest scene or open field, that’s a lot subtler.

Often the first thing I do to recreate an outdoor soundfield is cut some of the bottom end out of the voice, which helps. Then it’s a matter of constructing a subtle reverb where there are no reflections that allude to an indoor space…

TIME TO MIX – CHOP CHOP

AS: What makes a good film mix in your opinion?

RS: It varies from film to film of course. I suppose the most significant ingredient, from a film mixer’s point of view, would be time. Time is the crucial ingredient in any good mix. And the problem with that, of course, is that ‘time is money’. The budgets are getting smaller and smaller in Australia and film mixers are being made to do more for less, which is a shame. Soundtracks are now being made with half the funding, which makes the production of a quality soundtrack very difficult. And that’s driven by the fact that producers can’t get films up in Australia any more unless they’re perceived to be ‘low-risk’. And this means that either everyone ends up doing a lot of work for nothing, or the film doesn’t reach a level of quality that it deserves. In the end, time is crucial to the outcome.

But mixing a film is also about getting things right in the first instance. A lot of stuff that goes into a mix doesn’t ultimately get used, so editing the sound with refinement prior to it entering the final mix stage allows more time for the actual mixing. Meanwhile, if you’re editing and deliberating upon which pieces of audio need to be dropped from a scene and which should be kept, then that can be very time consuming.

AS: How do you determine which of these elements is superfluous to the production of a good film mix?

RS: The main aim is to produce a soundtrack that supports the story. That’s the soundtrack’s main purpose. It’s also important not to get in the way of the dialogue by putting in gratuitous sound effects that distract you from the storytelling. Putting in too many tricky sound effects, just for the sake of being tricky, can be a fatal error because these things take you ‘out of the film’, particularly if they’re panned in strange directions. In that situation you suddenly become conscious of the soundtrack.

Local film budgets have gone down and soundtracks are now being made with half the funding they used to, which makes the production of a quality soundtrack very difficult

SURROUND SOUNDINGS

AS: Are you wary of using surround sound channels too much then?

RS: I don’t like it when there’s an over-use of the surrounds. They’re good for ambiences and atmospheres because they’re the things you don’t see, so these sounds can be anywhere. Whereas sound effects like doors closing and gunshots – those sorts of sounds – I generally avoid placing ‘outside the screen’ because if they’re panned too extremely they draw too much attention to the soundtrack. It’s also a physical constraint of the cinema. By which I mean, although a door might appear on the left edge of the screen visually, that doesn’t mean you can mix its sound effect hard left because it will be too far away from the audience member who’s sitting down the front on the right.

Dialogue is probably the best example that illustrates this. Dialogue always comes from the centre speaker irrespective of whether or not two actors on screen are visually on the left and right. And yet, the mono placement of dialogue, in this situation, doesn’t sound unnatural to an audience. They’re not sitting in the cinema wondering why the panning isn’t representative of where the actors are placed on screen. Ironically, if you were to pan these elements so they literally reflected the position of the actors, it would sound less natural to the vast majority of audience members, who aren’t positioned in the centre of the cinema. That has to always be taken into account. I think a good film mix is one that’s pleasant and doesn’t take you ‘out of the film’ or distract you in a way that makes you conscious of the soundtrack. It’s all about illusion, creating an illusion of the senses that’s never disrupted by the soundtrack becoming conscious to audience members in and of itself.

AS: Is there a different mindset to film mixing to, say, mixing a record, where you’re anticipating that the listener will experience it over and over? Would it be fair to say that a film mix is more like a live gig in that you’re anticipating that most people may only experience it once?

RS: It an interesting question because, you’re correct in the sense that there’s no point hiding too many things so that the listener has something new to discover after their fifteenth listen. But there are those films that people go back and see many times – blockbusters that kids, in particular, see over and over. In the end though, as far as sound goes, I think all you’re trying to do is mix the elements so that each scene is as effective as it can possibly be, whether it be subtle or blatant.

MIXDOWN DELIVERY

AS: When you mix a film like Kung Fu Hustle, do you mix for the cinema audience primarily or with the future domestic DVD release in mind, or are these always two fundamentally different mixes?

RS: You actually do four mixes. You do a 5.1 Dolby Digital mix for the cinema – the ultimate setup played at 85dB – which is loud! Then you make a derivative two-track mix from that which is folded down through the Dolby matrix, which is itself then decoded back into four channels. Normally you just have to make minor adjustments to the cinema 5.1 mix to make sure you don’t have too much of the surround channel information in the stereo image. Then you do a DVD mix, which basically involves reducing the dynamic range by going back to the stems and applying different levels of compression to them. You also have to EQ the DVD mix differently because you’re no longer working behind the Dolby code, which creates a roll-off in the top end… so you have to soften the highs a bit. Finally your fourth mix is a stereo television broadcast mix, which has drastically reduced dynamic range so that people can listen to it at low volumes and talk over it. This final mix is always about making sure the dialogue is clear above all other aspects of the mix – all the sound effects, atmospheres and music have to stay well out of the way of the dialogue so it’s easy to understand at low volumes.

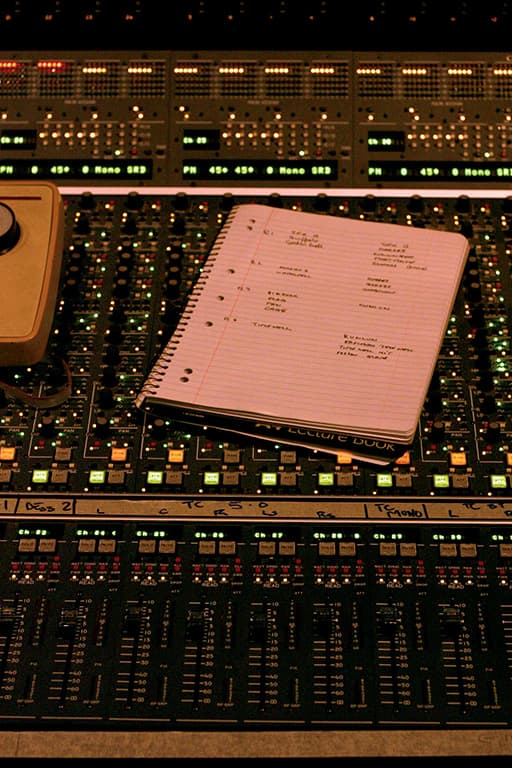

AS: What’s your favourite mixing platform these days?

RS: I’ve virtually always worked on a Harrison Series 12, and before that a Series 10. Harrison has a great automation system – the automation in the Series 12 is bullet-proof and I love working with it above all other film mixing consoles. The Harrison engine is very, very powerful and some of the Hollywood studios run as many as five and six hundred inputs through them – so the processing power required is enormous. Our recent addition to Soundfirm’s setup is the Smart AV console that we’re using with our Pyramix systems. The surface of the Smart is extraordinary. The great thing is that within your eye range you can see all these meters moving and all sorts of other information at a glance so you can be aware of 96 inputs and just access them so quickly and easily – it’s just amazing.

This is I think one of the major dramas for a mixer these days; being able to sort out what you want and don’t want in your mix quickly and easily. I know it may sound silly, but sorting out where things are coming from is an enormous task sometimes and that’s why Hollywood typically uses three mix engineers on a session. In Australia we’ve always been a single mixer country – two at best – so we need this efficiency of workspace and be able to gather things together under a manageable number of faders.

As far as platforms are concerned we’re using ProTools and Pyramix systems by and large. We exchange files between here and Beijing via our FTP sites. At our facility in Beijing we have several Pyramix systems that we use to edit the soundtracks.

Putting in too many tricky sound effects, just for the sake of being tricky, can be a fatal error because I find these things take you ‘out of the film’

FROM MIX TO MASTER

AS: Once you get to the final mixing stage, what’s involved in creating the final master?

RS: Mixing basically breaks down the sound into dialogue, sound effects, atmospheres, music, and group (which is other voices such as crowds etc). The editors who mix the effects (and there might be say three of them, for instance) may produce up to 64 or more audio tracks each which need to be pre-mixed down to four or five 5.1 stems. The editors volume graph it all prior to mixing. So if they’ve done their job, you can take that and decide what to adjust, whether to add bass or reverb. Because the editors generally premix these parts in isolation – or if they’re lucky they might have the dialogue or a rough music cue, which is always useful – it’s only at the final mix stage that the various premixes come together. Once all these various stems are brought together in the final 5.1 mixing stage, the audio is bussed out to the recorder as 5.1 stems of dialogue, music and effects – D, M & E. Sometimes you may split the effects into effects and atmospheres, so there might be four 5.1 stems that are recorded to the multitrack. These stems are then mastered through the Dolby meters, and by that stage you’re only making fine adjustments to the overall levels of those four stems – assuming you’ve done your job properly. You might add some limiting to contain the mix a bit, then you create a 5.1 master which is placed on a magneto optical disc and sent to the laboratory!

AS: How long does a mix generally take you?

RS: Usually the final mix takes about two weeks. Two weeks is an okay time frame but it’s largely determined by how successful the pre-mixing has been. And as I always say, mixing is as much about what you get rid of as what you keep. You’ve usually got too much…

LOCALS ONLY

AS: Are Australian films an ever-shrinking source of work for you or is it just a phase we’re going through?

RS: The local film industry has gone through an almost unprecedented decline in the last two years – it’s been an atrocious time for the industry. We used to make about 30 films a year and I think it was down to about 11 last year, so the state of the industry is pretty dire. Unfortunately we haven’t made any decent commercially successful films for a long time. The problem is that there’s no incentive provided by government, so private investment has all but evaporated without the tax incentives to encourage people to invest. And the television industry is suffering the same problems. The ABC isn’t making any decent dramas and commercial television is preoccupied with reality TV. The local industry is dependent upon commercial television drama and films for work. Cameramen and sound guys alike go back and forth from one to the other so without that investment and incentive from government, the industry has been largely crippled. And Soundfirm simply wouldn’t be here if we didn’t have the foreign work.

AS: Is the incentive to mix the Chinese films like Hero etc based entirely on financial considerations or are these films artistically satisfying as well?

RS: Working on films like Hero or House of Flying Daggers is incredibly satisfying and thoroughly enjoyable. I love doing them because I get involved in the sound design of them as well as the mixing stage, simply because I can. Australian sound editors get their noses out of joint during the production of Australian films because you’re ‘just the mixer’ – getting involved in the sound design causes a demarcation dispute. House of Flying Daggers for instance was done entirely in-house here at Soundfirm, and we actually won a Golden Reel award for best foreign film soundtrack for that, which was nice. It was up against films like Troy, King Arthur, Harry Potter, A Very Long Engagement and our other film, Hero. So we were pretty pleased about that. Of course we still haven’t received the award in the mail!

AS: Based on how you seem to treat your awards, I’m surprised to hear that you’re concerned about it?

RS: Yeah, I s’pose I’m not exactly the guy who puts the awards together in a magnificent glass cabinet. When it finally arrives it’ll probably just end up in a drawer somewhere!

RESPONSES